|

|

蘋果零售店 不肯說的秘訣

【聯合報╱編譯田思怡/報導】

2011.06.16 02:40 am

蘋果公司零售店有一套成功的銷售秘訣,要求員工嚴守紀律,不對顧客推銷而是協助解決問題。圖為去年七月十日上海浦東陸家嘴蘋果旗艦店員工在店外歡迎顧客的盛況。

(路透資料照) Approach(接觸)

Probe(探詢)

Present(介紹)

Listen(傾聽)

End(結尾)

華爾街日報根據被列為機密的蘋果員工訓練手冊、零售店會議紀錄並訪問蘋果前任和現任員工,歸納蘋果零售店的銷售秘訣:嚴格控管員工與顧客的互動、訓練員工現場提供顧客技術支援、考慮每個細節,細到示範用的照片和音樂都預先挑選。

據統計,現在每季光顧全球三百廿六家蘋果零售店的人次,比去年整年進入迪士尼四大主題樂園的六千萬人次還多。蘋果店面每平方英尺的年營收四千四百美元,超過蒂芙尼珠寶的三千美元。

蘋果零售店裝潢時髦,營造休閒氣氛,但蘋果公司對於零售店的運作守口如瓶。員工奉命不准談論有關產品的謠言,技術人員禁止擅自承認產品瑕疵,違反就開除。員工在半年內三次遲到超過六分鐘也會被炒魷魚。

根據訓練手冊,蘋果銷售人員奉行的銷售原則:不要推銷,而是協助顧客解決問題。「你們的工作是了解顧客的所有需求,有些需求連顧客自己都不知道。」員工拿不到佣金,也沒業績配額。

根據前員工提供的訓練手冊,蘋果的服務步驟藏在APPLE這五個字母中,A代表Approach(接觸),用個人化的親切態度接觸顧客;P代表Probe(探詢),禮貌地探詢顧客的需求;另一個P代表Present(介紹),介紹一個解決辦法讓顧客今天帶回家;L代表Listen(傾聽),傾聽顧客的問題並解決;E代表End(結尾),結尾時親切道別並歡迎再光臨。

分析家說,許多公司都追求好的服務和吸引人的店面設計,但少有公司像蘋果這樣規劃好每個細節。

華爾街日報十五日報導,蘋果公司以iPhone和iPad等高科技產品成為全球最有價值的科技公司,但蘋果另一項成功因素卻是低科技的零售店銷售秘訣,全藏在APPLE(蘋果)這五個字母中。

【2011/06/16 聯合報】

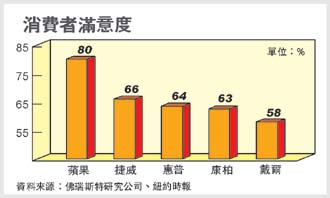

超越Google 蘋果成為全球最有價值品牌

【聯合晚報╱記者彭淮棟/即時報導】

2011.05.09 11:14 am

蘋果超越四連霸Google成為2011年全球最有價值品牌。臉書首度攻進全球百大品牌榜,而且一下站上第35名。戴爾落榜。年度全球「百大品牌」 (BrandZ Top 100)2006年首度推出,Google最近四連霸。蘋果在2009年還是老三。由於iPad和iPhone大獲成功,消費者和企業界都愛,蘋果品牌價值過去一年來突飛猛進,總計從2006年以來上升1370億億美元,升幅達859%。蘋果的股市市值已達3232億7000萬美元,是2006年的五倍多。任天堂退47格,降到79名。

【2011/05/09 聯合晚報】

德平板電腦 年需求50萬台

【中央社╱柏林28日專電】

2010.05.29 04:10 am

美商蘋果(Apple)的iPad平板電腦今天在歐洲開賣,德國各大城市出現搶購的人潮。業者預測,德國今年可望賣出50萬台的平板電腦。

柏林、漢堡、法蘭克福、慕尼黑的蘋果電腦專賣店,今天一早就有蘋果迷大排長龍,出現少見的熱鬧,不過搶購的熱度,與美國4月初開賣的瘋狂景象無法相比。

全國上千家高科技業組成的「德國資訊商業通訊新媒體公會」(BITKOM)今天表示,平板電腦去年才賣出2萬台,預估今年可賣出50萬台,銷售額暴增到3億歐元。

據BITKOM委託的民調,全德國有300萬人考慮買平板電腦,尤其中學生和大學生的意願特別高。

BITKOM表示,包含筆記型和平板電腦在內,德國今年可望賣出970萬台的行動電腦,比去年多100萬台。

瞄準iPad的熱潮,「明鏡週刊」(Der Spiegel)、「世界報」(Die Welt)等德國重要媒體,紛紛推出iPad版的付費版本,價格與紙本雜誌和報紙相當,「南德日報」(Sueddeutsche Zeitung)、「明星週刊」(Der Stern)也有意在近日內跟進。

【2010/05/28 中央社】

iPad在日上市 今秋販售電子書

【中央社╱東京28日專電】

2010.05.29 04:10 am

美國蘋果公司製造的新型平板電腦iPad今天在日本上市。由日本的主要出版社組成的業界團體今天決定,今年秋天起將提供人氣小說等約1萬冊在iPad上販售。

由日本31家出版社組成的「日本電子書籍出版社協會」(簡稱電書協)決定提供新服務,把加盟出版社過去出版的小說、實用書等約1萬冊加以電子化並透過iPad販售。

這些書籍包括(土反)東真理子所著的「女性的品格」和淺田次郎的「蒼穹之昴」等暢銷書。

電書協從6月起將先在蘋果牌手機「iPhone」等販售部分電子書,今年秋天開始在iPad販售。目前也正在思考是否提供給其他品牌的電腦。

在日本,電子書以藉由手機閱讀漫畫等為主流,但是電子書如果可以提供給iPad等多功能電腦,預料閱讀的風氣可更加普及。

另外,角川書店也決定今年秋天將單獨對iPad等的電子書終端提供新書、已發行的暢銷書和漫畫等數十冊。

角川書店為了與其他公司做商品區隔,正考慮影像結合電子書,以迷你電玩遊戲來誘導讀者閱讀電子書。

【2010/05/28 中央社】

紐周精選摘譯/賈伯斯有夢:人人買得起電腦…

2010/05/28

前言:蘋果超越微軟,成為全球市值第一的科技公司。蘋果公司創立34年來,營運曾出現危機,產品多次被看衰,全靠創辦人喬布斯發揮創意帶領蘋果逆轉勝。畢業季即將到來,聯合報特別選譯德國明鏡周刊專題報導,讓讀者認識喬布斯這位創意奇才和蘋果公司崛起故事。

【聯合報╱編譯張佑生】

34年傳奇 從家中車庫開始

蘋果傳奇始於一九七六年,賈伯斯家的車庫。賈伯斯和友人史提夫‧沃茲尼克自行組裝一台電腦,兩名年輕人有個偉大的夢想:推出一台人人買得起的電腦。

當年,電腦和周邊設備要價至少十萬美元,只有大公司和中情局買得起。一九七五年的某個周日早晨,沃茲尼克把兩條電線連結其中一台電腦的原型和螢幕及鍵盤。他笑說:「我當時並未發覺此舉的重要性。這是歷史上第一次有人在鍵盤上打字,字在螢幕上同步顯示。」

一九七六年四月一日,賈伯斯與沃茲尼克創立蘋果電腦公司;沃茲尼克主管研發,賈伯斯負責人事。一九七七年六月,蘋果二號電腦上市,定價一千二百九十八美元。這是第一部國民電腦,全球熱賣二百多萬台。

研發目標 就是要前所未見

一九七九年,蘋果開始研發新電腦。賈伯斯掌控研發部門,他要前所未見的東西。蘋果隨後推出以圖形使用者介面的麥金塔作業系統,馬上變成廣為大眾接受的介面標準。麥金塔是第一台大量生產的個人電腦,可開啟多個視窗,並有滑鼠。

賈伯斯說:「我們很清楚,以後世界上所有的電腦都會是那個樣子。」麥金塔電腦研發團隊核心人物安迪‧赫茲菲德說:「蘋果要做的不是獲利最高或技術最炫的產品,而是產品本身的完美就達到最偉大的境界。」

拚IBM 麥金塔不同凡想

一九八四年一月廿二日,職業美式足球總冠軍賽超級盃的中場休息時間,麥金塔電腦廣告登場,由好萊塢導演雷利史考特掌鏡。一排排面無表情的工人正襟危坐,注視著大銀幕上神似喬治歐威爾小說「一九八四」中的「老大哥」訓話。一名女子突然闖進會場,武裝警察緊追在後,女子將手中鐵鎚砸向銀幕,粉碎了老大哥的影像,解放了遭禁錮的大眾。

女子代表蘋果電腦,軍警則是蘋果當時的主要對手IBM。畫面傳來一段話:「一月廿四日,蘋果電腦將推出麥金塔,各位將了解一九八四為何不再像一九八四。」電視機前約八千萬名觀眾感到神奇,廣告專家認為這支廣告是曠世傑作。

蘋果的行銷策略和其他大企業並無不同:賦予產品讓消費者認同的情感及價值,買麥金塔的人都是既年輕又有創意,很酷。IBM的廣告標語是「想」(Think),蘋果就「不同凡想」(Think Different )。有誰不想「不同凡想」呢?

蘋果產品 新生活方式象徵

一九八二至一九八七年間,賈伯斯聘請艾斯林格的「青蛙設計」公司設計產品包裝,每月支付廿萬美元,賈伯斯要求交出「酷斃了」(insanely great)的設計。艾斯林格一九八四年設計出廿五款「加州白」的電腦,賈伯斯面露不悅,上市首日大賣五萬台,如今典藏在紐約惠特尼美國藝術館。

廿六年後,設計界與廣告界盛讚賈伯斯與艾斯林格的合作。其他電腦公司埋首於科技,蘋果強調功能與實用性,蘋果的產品變成一種新生活方式的象徵。

為誰當家 和史卡利鬧翻了

蘋果董事會在一九八○年想要延聘專業經理人掌舵,賈伯斯花了一年半的時間遊說百事可樂執行長史卡利跳槽。兩人合作愉快,卻在兩年後就因為誰當家做主的問題鬧翻,董事會在一九八五年解聘賈伯斯,史卡利比他多待了八年。

「董事會當時應該讓賈伯斯做主,我負責行銷即可,這樣我們就不會拆夥了。」蘋果的年營業額在史卡利的掌舵下從六億美元暴增到八十億美元,他會這麼說,是因為他認為賈伯斯能比其他人早廿年預見未來的趨勢,iPod和iPhone都是明證,史卡利自認沒有賈伯斯的本事。

賈伯斯後來再也不跟史卡利說話,讓他不勝唏噓。

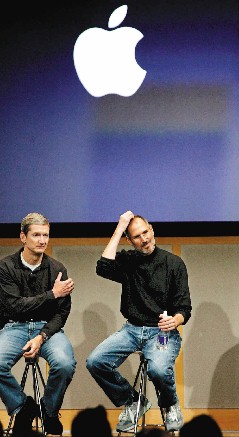

新品發表 員工榮耀加身時

沒有任何一位蘋果員工希望在電梯內遇見賈伯斯,因為他會連續發問:「你哪個單位的?做什麼的?公司為何需要你?」走出電梯時,賈伯斯可能會說:「我們不再需要你了。」

有些研發團隊總能獲得賈伯斯的青睞,資源和福利源源不斷。但是關愛的眼神會游移,所以各團隊會爭寵,搞小動作;賈伯斯只看成果。在蘋果撐得夠久,做到聯邦銷售部門主管的大衛‧索柏塔說,蘋果內部經常開會,但不會有決議,因為可能會惹毛賈伯斯。等到賈伯斯回家,隔天早上洗完澡,他可能會推翻前一天批准的事項。「直到賈伯斯上台開始演說,大家才知道下一步該怎麼走。」

蘋果的新品發表會是員工榮耀加身的時刻,但賈伯斯在發表會上很少唱名,僅說:「這是iPhone的研發團隊,請掌聲鼓勵。」

團隊起立、轉身接受讚美,賈伯斯點頭拍手。賈伯斯的戰士們在iPhone發表前,三個月間每天工作廿小時,為的就是這五秒。

【2010/05/28 聯合報】

21ST CENTURY PHILOSOPHER

(I)THE FOUNDER

2010/05/28

前言:蘋果超越微軟,成為全球市值第一的科技公司。蘋果公司創立34年來,營運曾出現危機,產品多次被看衰,全靠創辦人喬布斯發揮創意帶領蘋果逆轉勝。畢業季即將到來,聯合報特別選譯德國明鏡周刊專題報導,讓讀者認識喬布斯這位創意奇才和蘋果公司崛起故事。以下英文全文由紐時授權刊登。

【c2010 Der Spiegel/Distributed by The New York Times Syndicate】

The Apple story, which is Jobs’ story, can be described in six chapters, as told by six contemporary witnesses, each of whom spent time with Apple from its humble beginnings through to its current position as one of the most powerful companies in the world.

(I)THE FOUNDER

The Apple story begins in a garage in Los Altos, south of San Francisco, Calif. The setting is the Jobs’ family garage in 1976. Jobs and his friend Steve Wozniak are tinkering with a computer prototype. The two youths in T-shirts and cutoff jeans dream of great things: an affordable computer for everyone.

Each has a different role to play in that dream. Wozniak dreams of building the machine; Jobs wants to sell it.

Back then, computers were for rich companies and the CIA, enormous machines that cost $100,000 at least. However, Wozniak has been working on a new computer for 13 years. He knows he has talent and a feel for technology, yet he has no idea how revolutionary his talent will be. He first gets a glimpse on a Sunday evening in June 1975, when he takes two cables and connects one of his computer prototypes to a screen and a keyboard.

“I didn’t realize how significant that was,” says Wozniak. He laughs.

“It was the first time anyone typed a letter on a keyboard and the letter appeared on his computer monitor at the same time,” he wrote in his autobiography.

On April 1, 1976, the two friends found the Apple Computer company. Wozniak takes care of the technology while Jobs hires new employees – though not too many. There always has to be more work than employees, he says. Jobs finds an investor and organizes the sale of a product for which no market yet exists.

In June 1977, the Apple II computer is introduced to the market. Price: $1,298, including keyboard, excluding monitor. It’s the first computer for ordinary people, and it becomes a worldwide sensation, with over 2 million in sales. A beginning.

“Everything we made turned into gold, really nothing existed, everything was brought into the world for the very first time,” says Wozniak. But he leaves Apple in 1985. “Steve saw (the personal computer) as the future of a company, I saw it as my entire life,” he says, “I didn’t want to be in the limelight anymore.”

(II)THE MAGICIAN

In a world of high-resolution interfaces and sensory touch screens, it’s easy to forget how a PC looked in the early `80s. Green type glowed on a black background; commands were entered by keyboard. A PC was something for technology fans alone.

In 1979, Apple begins work on a new computer. Jobs soon assumes leadership of the development department; he wants something unprecedented. The Macintosh is supposed to reflect how its developers see the world. The Mac proves to be the first mass-produced PC with a graphical interface and windows that can open on top of one another. And it has a mouse.

“It was clear to us that every computer in the world would be like that in the future,” Jobs said years later.

Andy Hertzfeld, a key member of the Mac’s development team, says: “Apple doesn’t want to make a product that is the most lucrative financially or the most impressive technically. It should be the greatest thing in and of itself, simply perfection.”

The Mac is introduced on Jan. 22, 1984 in a 30-second commercial during the Super Bowl; the ad is filmed by Hollywood director Ridley Scott. You see endless rows of workers, a joyless army and a being like “Big Brother” from George Orwell’s apocalyptic novel “1984”; the army is IBM, at that time still an Apple rival. A young woman storms in followed by armed police. She shatters Big Brother and frees the enslaved masses. The woman is Apple. A voice announces: “On Jan. 24, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like '1984.”'

Almost 80 million television viewers are fascinated and bewildered. Advertising experts consider the ad to be the best in the industry’s history.

Apple succeeds in doing what most big companies only try to do: associate products with emotions and embellish them with values until the products themselves turn into values. Apple seduces. Whoever buys a Mac is young, creative and revolutionary, therefore cool. “Think different” later became Apple‘s slogan, and who doesn’t want to think differently?

(III)THE ARTIST

The house is like an Apple computer. White, wide and warm. On the outside are olive trees and palms, on the inside white walls and chrome, a grand piano, Chinese tea service, Meissen porcelain.

Hartmut Esslinger can speak both German and English; he has lived in California for decades. Esslinger is also the greatest designer in his world. Esslinger founded Frog Design in 1969, in a garage in Altensteig, which is in Germany’s Black Forest region.

“Design isn’t packaging. Design is a way of thinking, design thinks about the entire product,” Esslinger once said. “Design is not only how something looks and how it feels. Design is how something works,” Jobs said a few days later.

“Sometimes Steve hears something, then he presents it as his theory,” Esslinger says today, laughing. He regards Jobs highly, especially his boldness.

Jobs called on Esslinger because he needed a design for a graphical user interface, but Esslinger believes “that people sometimes don’t know yet what they want.” He also believes that “good design must find the exact balance between provocation and familiarity, or between absurd and boring.” That’s why he suggested something different to Jobs: white computers. “California white,” he called it. “The computer industry has never understood that people develop an emotional attachment to things,” he said. Naturally, Jobs also spoke this sentence, word for word, at a conference days later.

“Be insanely great” – those were Jobs’ orders. As the Frog people built prototypes, the artists and engineers were in constant exchange, and Jobs let them build. Frog received $200,000 per month – a lot of money for something that no one in the conservative Silicon Valley took seriously.

25 years later, designers and advertisers praise no cooperative effort more highly than the collaboration between Esslinger and Jobs. “Understand what people need. Develop things that make life easier and add joy. That’s the Apple secret,” according to Suze Barrett, creative director of the Scholz & Friends ad agency in Hamburg. While other computer companies were committed to the technology, “Apple focused on what is comprehensible and useful for people. So Apple products were a symbol of a new lifestyle, the 'digital lifestyle’ in which design plays the essential role.”

Apple’s devices look simple and functional. That idea was really stolen, from Braun pocket calculators for one, but Apple products remain what advertisers call “must-have products.”

The “i” that adorns essential Apple projects once stood for “Internet” and today stands for “I.” It’s about self-realization, or the illusion of it. “Must something be unusable if it’s art? Can’t art be something that’s usable?” asks Esslinger, who is now a professor in Vienna and writes books containing phrases like “seeing is believing, believing is seeing.”

Apple presented the first Esslinger computer, the Apple IIc, in Jobs’ office in Cupertino, Calif. – 25 models, all white. Jobs didn’t look pleased. “I hope it works,” he said. “I’m not convinced.” On the first day, Apple sold 50,000 units. That was on April 24, 1984. Today, the Apple IIc stands in the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City.

(IV)THE ENEMY

Jobs was never infallible, though he is worshipped. He wasn’t even always the “best CEO in the world,” as Google chief Eric Schmidt calls him. For a while, he wasn’t even CEO.

In 1980, after Apple’s initial public offering and the beginning of the company’s expansion, its board of directors want to install an experienced manager as head, one who can supervise the difficult Jobs, and show him how a global company can be run: respectably.

Jobs doesn’t put up a fight, but he wants to have a say in the selection, and he only wants one man: John Sculley, head of Pepsi-Cola, a marketing expert clueless about the computer business. He courts Sculley for 18 months, then finally Jobs says: “Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water or do you want a chance to change the world?”

Sculley accepts. And Jobs likes Sculley: They hike together in the hills of Northern California. The press calls them the “Dynamic Duo.” But after two years Sculley and Jobs have a falling-out. Things had devolved into a showdown: Who has the power, the founder or the manager? The one with vision or the respectable one? The board decides in favor of Sculley. In the fall of 1985, Jobs leaves Apple – his baby, his life.

Sculley remains. For eight more years.

“I believe it was a huge mistake to take me on (the job) as CEO,” says Sculley in early 2010. He is sitting at a solid conference table in New York City, with a window overlooking Central Park behind him. “The management board should have made Steve head.”

Why would he say something like that? What CEO downplays his own achievements? Shouldn’t he talk about how the company grew under his leadership from $600 million in turnover to $8 billion? “They should have just left the marketing to me, a board position or something like that,” says Sculley, “then Steve and I would never have separated.”

Jobs never spoke to Sculley again. “I believe he’ll never forgive me, and I understand him,” says Sculley. He looks tired. He is 71, a partner in a private equity firm, with an estate in Palm Beach, Fla., but after all these years he still suffers from Jobs’ withdrawal of affection.

Unfortunately, he himself was not talented enough “to build products or to look into the future like Steve,” says Sculley. In 1993, he had to leave Apple as well. The company was in a blind alley, devoid of ideas and without leadership, and therefore bound to lose against the new star of the computer world: Microsoft.

“Fortunately, Steve is there again,” says Sculley.

What makes him a genius, Sculley says, is Jobs’ ability to recognize, 20 years before everyone else, what will be standard in the distant future. “And Steve can do just that, he proved it with the iPod, he proved it with the iPhone, why shouldn’t he do it now in other areas as well?”

V. THE WOMAN WHO UNDERSTANDS THE MAN

“Steve is like all geniuses,” says Pamela Kerwin, “whoever said Mozart was a good person?” She laughs. And then she says: “Yes, he can be harsh and contemptuous, but he’s a visionary. And other managers want money and power, but he’s driven by the big idea. He has the ability to give birth to outstanding technology, and he’s never concerned with small steps – he wants whatever he makes to have a massive influence on the entire world.”

Kerwin is one of few women at the center of Jobs’ world. She is also one of the few people in his world who are able to take a reflective look at Jobs. She can say what she thinks of Jobs without falling into a state of shock, without fearing the withdrawal of warmth.

Things are pretty infantile in the Apple empire. Sometimes, a woman like Kerwin seems like the only adult there.

Perhaps it’s because she was never with Apple; Kerwin was from Pixar. Jobs took over her outfit in 1986 and then shook things up. Perhaps it’s because she was a teacher on the East Coast – a specialist in digital learning – before she came to Silicon Valley in 1989. She’s blond, wears glasses and a black turtleneck; she sits in the basement office of her house in Mill Valley, Calif.

Pixar, founded at the end of the ‘70s as a branch of George Lucas’ film empire, wasn’t yet one of the most successful studios in movie history, but one of several hundred startup companies in California. There was an idea, a handful of gifted people, parties and a lot of work. The grand old times. There was this uncertainty: Will we survive?

It’s not easy to create 3-D pictures. Pixar could do it, Jobs saw. “Back then, all of Silicon Valley said that he would sink his money into Pixar. He saw something that no one else saw. I think you could call that courage,” says Kerwin. Jobs gave Lucas $5 million and put up $5 million more for the company, and a journey began for the young people at Pixar.

Jobs hired creative types, but especially people “with developed left brains,” Kerwin says. Jobs didn’t really understand how the software worked. “When it came down to it, he didn’t understand what we were doing,” says Kerwin. “That probably protected us from him.” Certainly he yelled. Yes, he was punishing. He was moody. But he let animator and director John Lasseter, the main creative force at Pixar, take care of things.

Jobs sold Pixar’s services to Disney. “He could swim with the sharks, we couldn’t,” says Kerwin. “Steve wanted $10 million for everything he had to sell, always $10 million, even if it wasn’t worth $10 million.” He destroyed months of work. In negotiations with people from Intel, Jobs was in a bad mood shortly before the signing; Jobs swore, Intel was upset.

Kerwin says: “He’s not especially good at doing business with other important managers because then it’s ego against ego, and Steve never retreats, not even one step. But when he’s selling products to customers in jeans and a black turtleneck, like a messiah at these presentations, then he’s a brilliant showman. In that case, a big ego doesn’t interfere. An emcee needs a big ego.”

He changed Pixar’s direction: Animated pictures turned into short films, which turned into cinematic films. The screenplay for “Toy Story” was written, Jobs prepared the IPO. “Back then, all of Silicon Valley said this could never work, that a company that still hadn’t made a single dollar of profit was going on the stock exchange,” says Kerwin. “Toy Story” came out. Many years later, “Finding Nemo” followed. Those at Pixar who had made the journey with Jobs became millionaires.

And Jobs learned. He absorbed, took things apart, put them back together again, thought once more. He returned to Apple with the Pixar ideas. Animated pictures. Linking forms of communication. Mass media.

In August 1998, the iMac is introduced to the market. The response is tremendous, sales figures are great. But much more importantly, the fans are blown away. The Apple cult lives again. The slogan “think different” transforms Apple customers into allies, rebels against the mainstream, against Microsoft, fighting for personal individuality.

That’s the image, but it lies. Jobs is no longer a rebel: His company is about monopoly, market dominance. The next ruler always follows the revolution.

Jobs isn’t exactly a gentle person, according to all reports. He hates Bill Gates. Jobs was sick, perhaps he still is, and he hates his own young, healthy employees – in any case, that’s what young, healthy people at Apple say.

His natural parents are the Syrian political scientist Abdulfattah Jandali and the American Joanne Schieble; Paul and Clara Jobs adopted him. He grew up California, in Mountain View and Los Altos. Steven Paul Jobs was about 30 years old when he learned the truth. He began to look for his natural sister, Mona. He found her and they became friends. Then Mona wrote “A Regular Guy,” a novel. She told of a multimillionaire who “was too busy to flush the toilet,” who gave his ex-girlfriends houses so they would keep quiet; a narcissus who demanded that his lovers had to be virgins. Steve? It was never denied.

The actual Jobs was a fan of the folk singer Joan Baez. He said that he valued “young, superintelligent, artistic women.” In 1977, Jobs fathered a daughter, Lisa, with his then-girlfriend Chris-Ann Brennan. But they separated and he then refused to recognize the paternity. Chris-Ann and Lisa lived on welfare until Jobs was taken to court by the state for recognition of paternity. In a signed document, Jobs stated he was sterile and infertile and therefore physically incapable of fathering a child. The court forced him to take a blood test, which determined that he was the father; still, he refused maintenance payments. Finally, Jobs settled for monthly payments of $385.

In 1991 he married Laurene Powell; the couple now has three children.

A balanced life? Can a man who has this career behind him doubt himself?

About 10 years ago, Apple was worth $5 billion; today it’s worth over $240 billion. In 2006 Disney paid $7.4 billion in stock to acquire Pixar.

前言:蘋果超越微軟,成為全球市值第一的科技公司。蘋果公司創立34年來,營運曾出現危機,產品多次被看衰,全靠創辦人喬布斯發揮創意帶領蘋果逆轉勝。畢業季即將到來,聯合報特別選譯德國明鏡周刊專題報導,讓讀者認識喬布斯這位創意奇才和蘋果公司崛起故事。以下英文全文由紐時授權刊登。

【c2010 Der Spiegel/Distributed by The New York Times Syndicate】

(VI)THE SOLDIERS

Nobody at Apple wants to meet Jobs in the elevator, because then he’ll start asking questions: “Who are you? What are you working on? Why do we need you?” And when he gets out he’ll say: “No, we don’t need you anymore.”

Some teams always work in the spotlight – in other words, under Jobs’ eyes. These teams get all the resources and money, all the privileges in the world. But the spotlight wanders around campus. That means lively company politics, a lot of talking. Everyone wants someone’s attention, and everyone wants Jobs’ attention. But Jobs wants results; nothing but results really interest him. The best managers, the real heroes at Apple, are those at whom Jobs shouts most often – and who, in spite of that, speak calmly to their subordinates.

One employee who was there for a long time – until he got fired – is David Sobotta. He says that such uncertainty is “inherent in the system.” Sobotta sold what was developed in Cupertino. The Army, NASA and American universities were his customers. Today he lives in Roanoke, Va., high up on the mountains. “It extends throughout the company,” says Sobotta: “Nobody wants to decide anything, because a decision means that Steve can get mad. There’s a lot of dead meat at Apple.”

“Dead meat” being a cynical term for those people who could just as well be unemployed, and nobody would notice it.

Sobotta says that it was once different; those were the years without Jobs. “There were the golden Apple sales trips” – trips to Paris, Sydney, Vienna, for the upper 10 percent, the most successful sellers. With the new leader, everything was different. Better on the one hand, but on the other the new leader was once again named Steve Jobs. Sobotta flew to Cupertino with generals and professors, but never once secured an appointment with Jobs, never received a promise that he would actually appear in person – always only a hint. “But the generals flew in, all of them wanted to be near Steve,” according to Sobotta. And sometimes Jobs appeared “in shorts and Birkenstocks, unshaven, and he never answered questions. He always just talked about the subjects he wanted to talk about. But the room heard him. Always,” says Sobotta.

Apple is a meeting company. They have meetings constantly, but nothing is decided. Then Jobs goes home. He goes to think. He has learned to trust his instincts; for years he’s been hearing that he’s a genius. For that reason, he’ll take showers in the morning and bury projects that he approved only yesterday. “No one knows what’s going to happen until the moment Steve goes on stage and addresses the faithful,” says Sobotta.

These are the moments of glory for Apple’s army. It’s all about these moments, for naturally the soldiers get paid well, but not outstandingly well; they get their pay plus bonus plus shares; they say that what counts are those fleeting moments in Jobs’ spotlight.

Jobs seldom names names on these occasions. He simply says, “This is the team that developed the iPhone. A round of applause, please.”

They stand up. They turn. Jobs nods and claps. That’s all they want, these five seconds, that’s what they’ve been working for for three months, 20 hours a day.

Could Apple be more successful if things were managed differently? With respect, with communication, like a modern company?

Since Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, the annual turnover spiraled up from a solid $7 billion to almost $43 billion. The share price rose from about $5 to over $260. In 2009, Apple made a profit of $8.2 billion. With 34,000 employees, that means a solid $240,000 profit per employee.

Thirty-four years after it was founded, Apple is no longer a computer manufacturer. It’s not very easy to say what Apple is, and somewhat harder to guess what Apple will be in the future: an electronics giant? An inventor of lifestyle products for the digital age?

How music is consumed, produced and sold today is different than 10 years ago. Tens of thousands of songs fit onto an iPod – a complete music collection in your pocket, always ready to be played. Large companies were brought to their knees because of it – because of iTunes, that is. Once Apple took over, music stopped being sold almost anywhere but through online stores.

The iPod turned into a phenomenon, into a “life-changing cultural icon” as Newsweek wrote three years after the device appeared; Apple had sold a good 3 million iPods at that point. In the past three business years alone, the company has sold 160 million units.

Now, with the launch of the iPad, publishing houses and media companies are racing to build something for Apple’s new gadget. They want to offer their books and magazines in electronic form on the iPad, a device Jobs naturally calls “magical” and “revolutionary.”

The iPad won’t just be a gift for magazines, newspaper companies and television corporations. They have high hopes of attracting new readers and viewers, and above all, endless new revenue. They all hope that money can be earned with old products, even in the digital age. Newspapers and magazines offer iPad applications for their print editions, with extras similar to those offered on their online sites: videos, interactive graphics. The intent is to lure readers into paying for digital editions, perhaps more than for the print edition.

All this in turn lures advertising customers, since they can make advertising more vivid and interactive with, for example, embedded videos. Time magazine is charging $200,000 for an advertisement in its first iPad edition.

But naturally Jobs knows all that – that’s the reason he developed the iPad in the first place. Jobs hopes to transform multiple branches of industry and bind them to Apple all at the same time. Apple will have a say in how a magazine looks so it can be read on the iPad, and how much money the publishing company will charge for this service.

Isn’t a new market dominated by Apple better than no market at all?

That may be. In any case, Jobs’ competitors say that Apple’s dominance will come to an end with the iPad, because the market will become so saturated with the company’s products. The Apple decade will come to an end. But that’s probably not the case. More likely, the coming decade will be even more successful for the company than the previous one, because Apple has the entertainment market within its grasp. And Apple is constantly growing, expanding as it always is into other, newer areas of modern life.

It is also possible that the company will continue on for a while longer and then, very abruptly, the iWorld will collapse. For good, if Jobs himself collapses and it becomes clear that his company isn’t prepared for life after Jobs.

+++

The first time Jobs was absent was in 2004, it was due to pancreatic cancer. The doctors said the operation would save him and he would live at least 10 years longer. But Jobs hesitated. The pope of technology didn’t trust modern medicine. Jobs, a Zen Buddhist and vegetarian, preferred alternative methods. A diet, the pellets his nonmedical practitioner recommended. Jobs refused the operation for nine months, and during these nine months had discussions with the board of directors about whether he had to inform shareholders about the disease and methods of treatment.

But since the board is made up of people who revere Jobs, they said nothing.

On July 31, 2004, Jobs had the operation. On the next day he wrote an e-mail to employees: He had had a life-threatening disease, but now he was healed.

Five years later he was absent again. He needed a new liver, and naturally he got it quickly. From “a young man in his 20s, who died in a car accident,” according to Jobs. In the middle of 2009 the ruler returned to his empire, acting like everything was as before, but that wasn’t the case.

“It felt like late Rome,” says one person, who was there during those periods. Before Jobs was away for long, it was clear that no stable structures or rules existed: not for product development, not for communication. Was Steve’s thumb up or down? That was the only thing that counted.

But now, “The emperor was sick, and all the senators were arming their private armies and wanted power,” says the former employee, who would know. There were acts of vengeance: Those people who had come up with Jobs, lost their jobs and were excluded from all important discussions. “Products were announced and retracted, others were developed rashly and shot down again. Everything was company politics.”

Jobs was absent, and Apple employees were unsettled.

When the company has to carry on without Jobs, according to Hertzfeld, the Macintosh developer, then it would be better if at first it acted according to a plan. Customer needs could be taken into account; Apple could relearn things, like humility. After a while, however, Hertzfeld also says “the drive to create the best possible things would be missing.” And Apple would become a company like a thousand others.

The boss generally doesn’t like to talk about himself – in any case, he doesn’t say anything about his weaknesses. That time at Stanford, however, on a hot June day in 2005, when he spoke to students at the university stadium and made a speech that was like a confession, he finally told his third story: the story of life and death.

As a young man, Jobs said, he encountered a quotation: “When you live every day as if it were your last, you’ll be right sometime.” Since then, he has always asked himself whether he’s doing what he wants to do in case today is his last day. If the answer is “no,” he changes the plan.

He gulped. Then Jobs told Stanford that a year ago at 7:30 in the morning he was at his doctor’s office. The diagnosis: pancreatic cancer, incurable. He still had three to six months to live. “Get your personal affairs in order,” the doctors said.

“I lived with the diagnosis. On that same evening, I had a biopsy,” Jobs said.

The doctors inserted tubes, withdrew tumor cells, examined them. An operation could probably cure him after all. He was a rare exception, they said.

Is there a moral? There’s always a moral. “Your time is limited. Don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma, which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice. And, most important: Have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become.”

And finally he spoke his closing words: “Stay hungry. Stay foolish.”

本文於 修改第 3 次

|

本城市首頁

本城市首頁

一般公司的情形是設計師必須聽令於製造部門,但在蘋果,設計師的話才是聖旨。

一般公司的情形是設計師必須聽令於製造部門,但在蘋果,設計師的話才是聖旨。