|

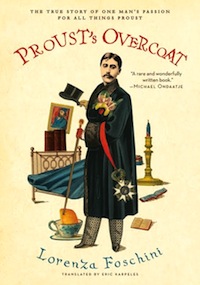

My book review about《Proust’s Overcoat》

My book review about《Proust’s Overcoat》

|

瀏覽7,683 |回應1 |回應1 |推薦1 |推薦1 |

|

|

|

My book review about《Proust’s Overcoat》

“The Celtic belief that the souls of those we have lost are held captive in some lesser being, in an animal, a vegetable, an inanimate object, in effect lost to us until the day, which for some of us never comes, when we find ourselves walking near a tree and it dawns on us this object in their prison. The souls shudder, they call out to us and as soon as we have heard them, the spell is broken. Liberated by us, they triumph over death and come to live among us once again.”

(In Search of Lost Time Vol.1: Swann's Way)

This is a simple and heart-stirring story about a bibliophile searching for a writer’s relic.

What Proust leaves us posthumously? There are should be invisible and invaluable treasure like his works, his thought, his philosophy of life, but I never think of his remains like his manuscript, his furniture, even his coat.

Why does this story make me intoxicated? In another word, I wonder why a coat causes intoxication to a man all his life?

I don’t know whether it is belongs to the fetishism, but from this story I realize someone’s passion for Proust really surprised me, even surpass me more than thousand times.

The true story begins when a journalist visits Carnavalet Museum in Paris. From her interviewing a costume designer, Piero Tosi, she knows something about Jacques Guérin who has obsessions with a writer's personal objects.

Who is Jacques Guérin? He is a lucky guy and it is his destiny to make the acquaintance of Proust’s brother and sister-in-law. And he is on his journey in search of Proust’s Overcoat.

Please find the plot as below that I quoted from Amazon’s Product Description.

http://www.amazon.com/Prousts-Overcoat-Passion-Things-Proust/dp/0061965677

Jacques GuÉrin was a prominent businessman at the head of his family's successful perfume company, but his real passion was for rare books and literary manuscripts. From the time he was a young man, he frequented the antiquarian bookshops of Paris in search of lost, forgotten treasures. The ultimate prize? Anything from the hands of Marcel Proust.

GuÉrin identified with Proust more deeply than with any other writer, and when illness brought him by chance under the care of Marcel's brother, Dr. Robert Proust, he saw it as a remarkable opportunity. Shamed by Marcel's extravagant writings, embarrassed by his homosexuality, and offended by his disregard for bourgeois respectability, his family had begun to deliberately destroy and sell their inheritance of his notebooks, letters, manuscripts, furni-ture, and personal effects. Horrified by the destruction, and consumed with desire, GuÉrin ingratiated himself with Marcel's heirs, placating them with cash and kindness in exchange for the writer's priceless, rare material remains. After years of relentless persuasion, GuÉrin was at last rewarded with a highly personal prize, one he had never dreamed of possessing, a relic he treasured to the end of his long life: Proust's overcoat.

Proust's Overcoat introduces a cast of intriguing and unforgettable characters, each inspired and tormented by Marcel, his writing, and his orphaned objects. Together they reveal a curious and compelling tale of lost and found, of common things and uncommon desires.

Inside the story, I am deeply touched by the occasion that Jacques Guérin had seen Proust's manuscripts as the author describes:

“Now, seated in the oppressive office of Proust’s brother, he understood the full impact of this word fin, written with such clarity and force, detached from the body of the text. “

(P.29~30)

It seems that we can image this word “fin” so powerful, resolute and satisfactory to reflect Proust’s devotion of his whole life to complete his magnum opus.

Although Alain de Botton reminds us that “a genuine homage to Proust would be to look at our world through his eyes, not look at his world through our eyes.” I still believe that we owe to Jacques Guérin who strives to protect Proust’s remains from the destruction by Proust’s family, and therefore we have the chance to visit Proust’s room reconstructed at Carnavalet Museum.

How wonderful Proust’s life is!How wonderful Guérin’s life is!

However I wonder what my life is?

【Reference】

About the Author

http://www.harpercollins.com/author/microsite/About.aspx?authorid=36713

Lorenza Foschini is an Italian journalist, writer, and television news anchorwoman on RAI, the state-owned Italian radio and television network. As a Vatican correspon-dent, she traveled around the world, covering the journeys of Pope John Paul II. She is the author of Investigation at Millennium’s End, which won the Prix Scanno, and has translated Return to Guermantes, a collection of previously unpublished Proustian texts, from French into Italian. Born in Naples, she lives in Rome.

http://www.bookforum.com/review/6183

Proust's Overcoat by Lorenza Foschini

Lauren Elkin

In the preface to his translation of John Ruskin's Sesame and Lilies, Marcel Proust wrote that while some people decorate their rooms with things that reflect their taste, he preferred his room to be a place "where I find nothing of my conscious thoughts, where my imagination is thrilled to plunge into the heart of the not-me." Anyone who has stood looking at Proust's reassembled cork-lined bedroom at the Musée Carnavalet in Paris—his armchair, his pigskin cane, his brass bed—and tried, unsuccessfully, to feel kinship with his spirit would be relieved to know that he had such a desultory relationship to his personal possessions.

These remnants of Proust's physical life survive because of the obsessive quest of one man: Jacques Guérin, a perfume magnate and bibliophile who rescued Proust's effects from a fate worse than oblivion—destruction at the hand's of Proust's sister-in-law, Marthe. In Lorenza Foschini's new book, Proust's Overcoat, the author tells the story of how Guérin discovered and claimed, piece by piece, what was left of Proust's belongings, elegantly teasing out the relationship between family dynamics and property. Foschini also highlights the role of objects and spaces in Proust's work, allowing us to see In Search of Lost Time through a different lens. The result is an oblique kind of literary criticism, a material commentary on one of the masterpieces of the twentieth century.

Guérin came into the Prousts' lives by accident, when an illness led to his being cared for by Dr. Robert Proust, Marcel's younger brother. Guérin discovered that Dr. Proust had all of Marcel's furniture, as well as his manuscripts, letters, books, photographs, and paintings. Through Guérin's relationship with the Prousts, we learn of the role Robert played as his brother's literary executor, exerting tight control over the publication of Marcel's posthumous works, including holding back the manuscript to the last volume of In Search of Lost Time: "In 1926, four years after Marcel Proust's death," Foschini writes, "Robert Proust was still the only person alive who knew what happened in Time Regained."

While Robert kept strict control over his brother's literary legacy, his wife, Marthe, was hell-bent on destroying it, systematically ripping out the dedication pages from Marcel's books and burning large amounts of his papers—at least until someone told her how much money they were worth. After Robert's death in 1935, his wife and daughter vacated the apartment immediately, leaving behind Marcel's desk and bookcase. Guérin was taken to the Proust apartment by the family's agent to buy some of the abandoned furniture. There, in the "plundered, devastated" apartment, he "keenly felt the presence of Proust." The furniture "seemed to be appealing to him for help" and Guérin bought it for 1,500 francs.

Foschini links Marthe's acts of destruction to the Proust family's resentment of Marcel's homosexuality, which, she writes, "surrounded him like an invisible and insurmountable wall. His family's unwillingness to understand led to a history of silences that mutated into rancor. This in turn was transformed into acts of vandalism—papers destroyed, furniture abandoned." But Marcel was certainly no innocent victim; Foschini writes that he shocked his brother and sister-in-law by giving some of his parents' furniture to a brothel, as does the narrator in In Search of Lost Time: "I never went back to this Madam's house, because those pieces of furniture seemed to be alive and beckoning me."

The idea of furniture being somehow alive underscores why Marthe would have tried so ardently to rid herself of Marcel's furniture and belongings; it also explains why Guérin came to think of himself not only as a collector but as an "agent of destiny," going so far as to crash the funerals of Proust's friends, "in search of more confidences, more souvenirs."

Given the abundance of Proustian objects Guérin collected, it's fair to wonder why Foschini concentrates on the overcoat. But then, the fur-lined coat seems the most tactile of relics—one can imagine bits of Marcel's DNA nestled among its fibers (even as one concedes it must have been laundered). It's a warm, enveloping, womblike garment; Marcel would wrap himself in it, as it gave him an extra layer of protection from the world. It was an intrinsic part of Proust's "look," which one of his biographers, Léon-Pierre Quint, described as "a cross between a refined dandy and an untidy medieval philosopher."

"The ultimate relic," Foschini calls the coat, "so evocative of the physical form of the writer." If, as Proust himself held, objects have the souls of people trapped inside them, it is easy to imagine that if Proust's own soul is trapped anywhere, it's in the overcoat—which, being too fragile for display, is housed in the Musée Carnavalet's storeroom. Perhaps if it were out along with Proust's other belongings, a visitor to the Carnavalet might, like Guérin, keenly feel the presence of Proust.

http://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2010/08/30/in-search-of-prousts-overcoat/

In Search of Proust’s Overcoat

August 30, 2010 | by Stephanie LaCava

Proust’s Overcoat tells the story of Jacques Guérin, a Parisian perfume magnate, who was obsessed with the works of Marcel Proust. In 1929, through a chance connection, he met Proust's family, only to discover that they intended to destroy the author's notebooks, letters, and manuscripts. Guérin ingratiated himself with Proust's heirs, and through bribery and kindness, amassed a collection of Proust's belongings and manuscripts, saving it from destruction. I recently exchanged e-mails with Lorenza Foschini, an Italian journalist, about her book.

Why was Proust’s overcoat so special?

Proust's contemporaries, like Jean Cocteau, described his style as embodying an old, refined elegance. He was a real dandy, always dressed in large silk shirtfronts by Charvet, a double-breasted waistcoat, very light colored gloves with black points, a flat-brimmed top hat, a rose or an orchid in a buttonhole of his frock coat, and a walking cane. But even on the hottest days, Marcel didn’t remove his heavy fur-lined coat. This became legendary among those who knew him.

How did you discover this story?

Those who love Proust know that such passion often becomes a mania. This was so in my case. When interviewing the well-known Visconti costume designer, Piero Tosi, I could not resist the temptation to ask him if he knew the reason why the great filmmaker (Luchino Visconti) stopped production on his beloved project, bringing In Search of Lost Time to the big screen.

In the early seventies, the American studios allocated a lot of money for this project and there was talk of casting actors like Laurence Olivier, Marlon Brando, Dustin Hoffman, even Greta Garbo. Tosi was invited to Paris to go over production plans. It was there that he met a very special person. My book comes from the extraordinary story that Tosi told me about this man, Jacques Guérin.

I can understand the need to collect the letters, diaries, and notes of a writer. But can you explain our obsessions with a writer's personal objects? Why a bed? A rug? A coat?

It's because of Guérin that a draft of Swann's Way became available to us. The same goes for several versions of the last volume of In Search of Lost Time.

My book is a story about the incredible efforts of a great bibliophile. Guérin was able to save important papers that offended the bourgeois respectability of Proust’s prude sister in law. After Proust’s death, his family began to deliberately destroy and sell his notebooks, letter, manuscripts, furniture, and personal effects.

Proust's homosexuality surrounded him like an invisible and insurmountable wall. His family's unwillingness to understand this led to a history of silence that mutated into rancor. This transformed into acts of vandalism as his papers were destroyed and his furniture abandoned. Finding the coat is only the conclusion of a series of adventures and coup de théâtre that Guérin had to face. I do not want to reveal them now; you have to read the book.

Of all of Proust's objects collected by Guérin, which is your favorite?

If I were to answer, it would diminish the simple fetishism of Guérin's love for the objects, which he saved from flames. Proust writes in Swann's Way: “The Celtic belief that the souls of those we have lost are held captive in some lesser being, in an animal, a vegetable, an inanimate object, in effect lost to us until the day, which for some of us never comes, when we find ourselves walking near a tree and it dawns on us this object in their prison. The souls shudder, they call out to us and as soon as we have heard them, the spell is broken. Liberated by us, they triumph over death and come to live among us once again.” Guérin, for sure, had to know this.

I do love the bed that Proust had since he was sixteen, where he wrote his entire opus, and where he died on November 18, 1922. For Walter Benjamin, there were only two moments in history chronicling the rigging of such “scaffolding.” The first was when Michelangelo, lying prone, his head thrown back, painted the creation of the world on the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling; the second was the “bed on which the ailing Proust lay, pen in his raised hand, covering innumerable pages in writing consecrated to the creation of his own microcosmic world.”

What drives a collector like Guérin?

Jacque Guérin loved to define himself (despite having one of the greatest book collections in the world) not as a collector, but as a rescuer. He would say that his passion was to save rare books, manuscripts and photos from destruction and negligence.

When did your own fascination with Proust begin?

I was eighteen and I was in Naples where I was born (at that time, I was living in Rome with my parents). I was a guest of the man who would become the father of my daughter, Camilla. I couldn't sleep and found near the bed a Livre de Poche of Proust. I didn't sleep the entire night. I never left the book, and took the last volume with me on my honeymoon.

http://www.amazon.com/Prousts-Overcoat-Passion-Things-Proust/dp/0061965677

Review

“It’s exquisite, delicate, fascinating. I put PROUST’S OVERCOAT on the same shelf as Serena Vitale’s PUSHKIN’S BUTTON and Umberto Eco’s FOUCAULT’S PENDULUM.” (Edmund White, author of HOTEL DE DREAM and MY LIVES )

“A rare and wonderfully written book of literary detection, that is heartbreaking as well as thrilling, about the ‘afterlife’ of a writer’s manuscripts and the things he carried.” (Michael Ondaatje )

“This book is just my style. In the spirit of La Bohème, a brilliant aria to the coat.” (Patti Smith )

“Lorenza Foschini’s portrait of Guérin and his Proust obsession is delightful, and the objects themselves take on a life of their own and do a jig in this little volume.” (Los Angeles Times )

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mus%C3%A9e_Carnavalet

The Carnavalet Museum in Paris is dedicated to the history of the city. The museum occupies two neighboring mansions: the Hôtel Carnavalet and the former Hôtel Le Peletier de Saint Fargeau. On the advice of Baron Haussmann, the civil servant who transformed Paris in the latter half of the 19th century, the Hôtel Carnavalet was purchased by the Municipal Council of Paris in 1866; it was opened to the public in 1880. By the latter part of the 20th century, the museum was bursting at the seams. The Hôtel Le Peletier de Saint Fargeau was annexed to the Carnavalet and opened to the public in 1989.

|

|

|

|

August 30, 2010 | by Stephanie LaCava  Proust’s Overcoat tells the story of Jacques Guerin, a Parisian perfume magnate, who was obsessed with the works of Marcel Proust. In 1929, through a chance connection, he met Proust's family, only to discover that they intended to destroy the author's notebooks, letters, and manuscripts. Guerin ingratiated himself with Proust's heirs, and through bribery and kindness, amassed a collection of Proust's belongings and manuscripts, saving it from destruction. I recently exchanged e-mails with Lorenza Foschini, an Italian journalist, about her book. Proust’s Overcoat tells the story of Jacques Guerin, a Parisian perfume magnate, who was obsessed with the works of Marcel Proust. In 1929, through a chance connection, he met Proust's family, only to discover that they intended to destroy the author's notebooks, letters, and manuscripts. Guerin ingratiated himself with Proust's heirs, and through bribery and kindness, amassed a collection of Proust's belongings and manuscripts, saving it from destruction. I recently exchanged e-mails with Lorenza Foschini, an Italian journalist, about her book.

Why was Proust’s overcoat so special? Proust's contemporaries, like Jean Cocteau, described his style as embodying an old, refined elegance. He was a real dandy, always dressed in large silk shirtfronts by Charvet, a double-breasted waistcoat, very light colored gloves with black points, a flat-brimmed top hat, a rose or an orchid in a buttonhole of his frock coat, and a walking cane. But even on the hottest days, Marcel didn’t remove his heavy fur-lined coat. This became legendary among those who knew him. How did you discover this story? Those who love Proust know that such passion often becomes a mania. This was so in my case. When interviewing the well-known Visconti costume designer, Piero Tosi, I could not resist the temptation to ask him if he knew the reason why the great filmmaker (Luchino Visconti) stopped production on his beloved project, bringing In Search of Lost Time to the big screen. In the early seventies, the American studios allocated a lot of money for this project and there was talk of casting actors like Laurence Olivier, Marlon Brando, Dustin Hoffman, even Greta Garbo. Tosi was invited to Paris to go over production plans. It was there that he met a very special person. My book comes from the extraordinary story that Tosi told me about this man, Jacques Guerin. I can understand the need to collect the letters, diaries, and notes of a writer. But can you explain our obsessions with a writer's personal objects? Why a bed? A rug? A coat? It's because of Guerin that a draft of Swann's Way became available to us. The same goes for several versions of the last volume of In Search of Lost Time. My book is a story about the incredible efforts of a great bibliophile. Guerin was able to save important papers that offended the bourgeois respectability of Proust’s prude sister in law. After Proust’s death, his family began to deliberately destroy and sell his notebooks, letter, manuscripts, furniture, and personal effects. Proust's homosexuality surrounded him like an invisible and insurmountable wall. His family's unwillingness to understand this led to a history of silence that mutated into rancor. This transformed into acts of vandalism as his papers were destroyed and his furniture abandoned. Finding the coat is only the conclusion of a series of adventures and coup de theatre that Guerin had to face. I do not want to reveal them now; you have to read the book.

本文於 修改第 1 次

|

|

|